Off the Record

Horizon O

[3]

On Watching and Black Death Notices

Whose report will you believe? – Ron Kenoly, 1992

If it bleeds, it leads. – Eric Pooley, 1989

Across the past two weeks, American news outlets have circulated the image of officer Derek Chauvin killing George Floyd with chilling regularity. I have seen the footage more times than I can count. I offer seen here, rather than watched, in order to indicate something of the nature of the showing of that footage and of my own practices of consumption. By highlighting the act of having seen, I mean to distinguish a practice of viewing that is more brief and transitory than it is meditative—more unintentional than it is deliberate. To have seen this footage, in this context, is to have noted its presence momentarily; to have watched the same is to have given it extended consideration.

As a rule, I try to avoid repetitively taking in images of Black people being killed. I make determined choices about how and when I view video evidence of Black death, primarily basing these decisions on my mental health at the time and my access to beloved community members with whom to process what I’ve witnessed. I will not watch these videos while at work.

I have, in recent years, developed a number of feeble and neurotic tactics in an attempt to limit how often I see Black death spectacles and how habituated to them I become: refusing to click links to the videos when I come across them online; scrolling quickly past postmortem or in situ photographs of the Black dead on my phone and computer; even holding my hand up in front of my face to selectively constrain my field of vision when watching the news on television.

But it has been especially difficult to intentionally watch—or not watch—the killing of George Floyd. The picture of officer Chauvin, knee fatally grooved into Floyd’s neck, has become ubiquitous. News media coverage routinely transforms the entire murderous duration into a video bumper, a flash of content that pretends to convey everything the public needs to know about the annihilation of a Black life in a single visual burst. The picture of Floyd’s asphyxiation pops onto our collected visual feeds with irregular frequency. In live broadcasts, reporters bridge the transitions between shots of burning precincts and shambling protestors with the strategically placed still shot of Chauvin’s death-dealing genuflection.

Many of you reading these words will immediately recall the picture I am explicitly referencing here without my having to include it. To echo the observations of scholar Saidiya Hartman concerning Frederick Douglass’s description of the beating of his Aunt Hester, I hardly need to describe or display the photograph of Chauvin’s murder of George Floyd to conjure up the same widely-shared image for visitors to this digital space. The “terrible spectacle” threatens a macabre familiarity that rivals the horror of the murder itself; “Only more obscene…is the demand that this suffering be materialized and evidenced by the display of the tortured body or endless recitations of the ghastly and terrible.”[1] As of this writing, the indelible image of Chauvin kneeling on George Floyd’s neck—excerpted from 17 year-old Darnella Frazier’s recording of the event—remains the focal point for the Wikipedia web page dedicated to the “Killing of George Floyd.”

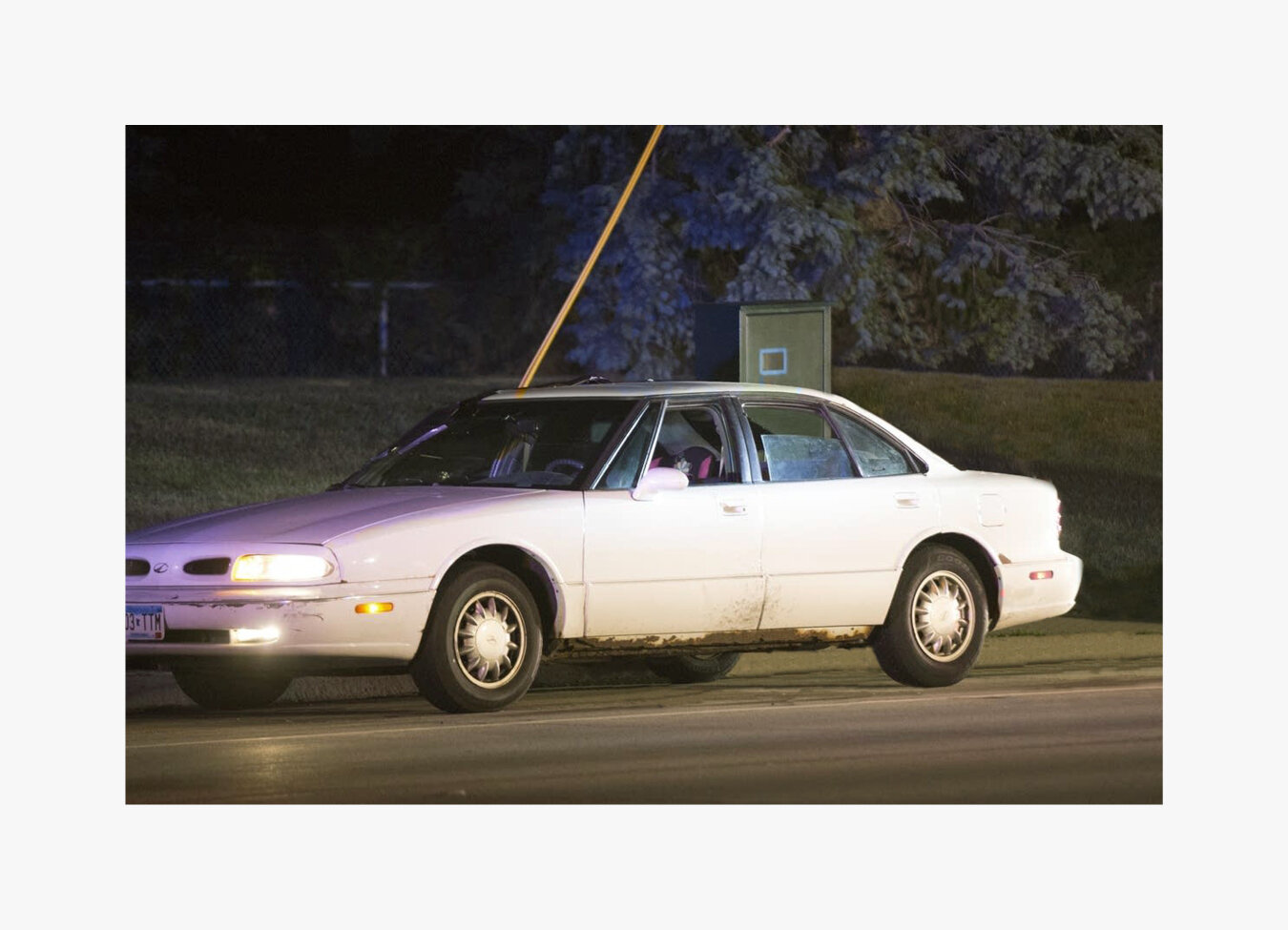

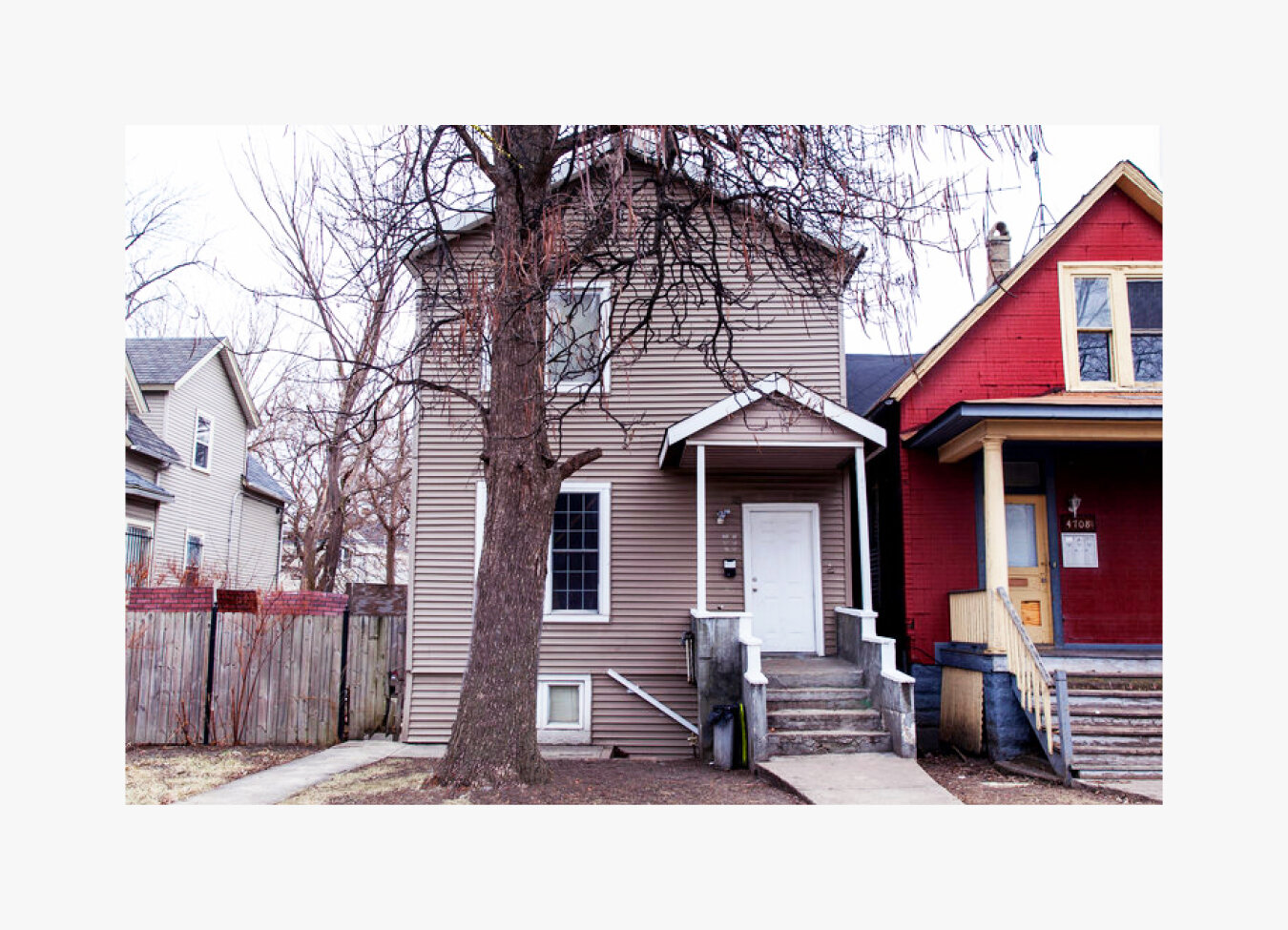

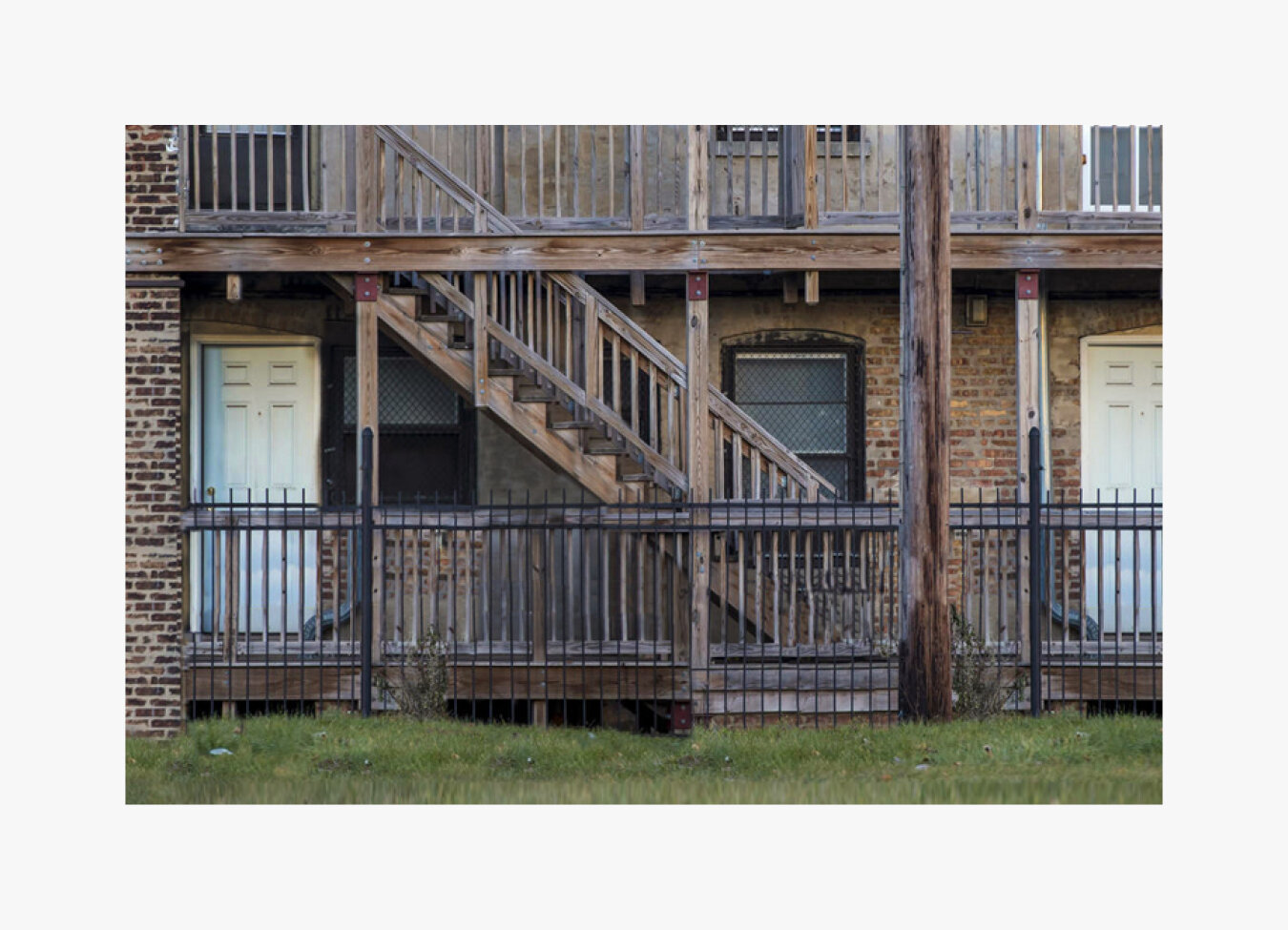

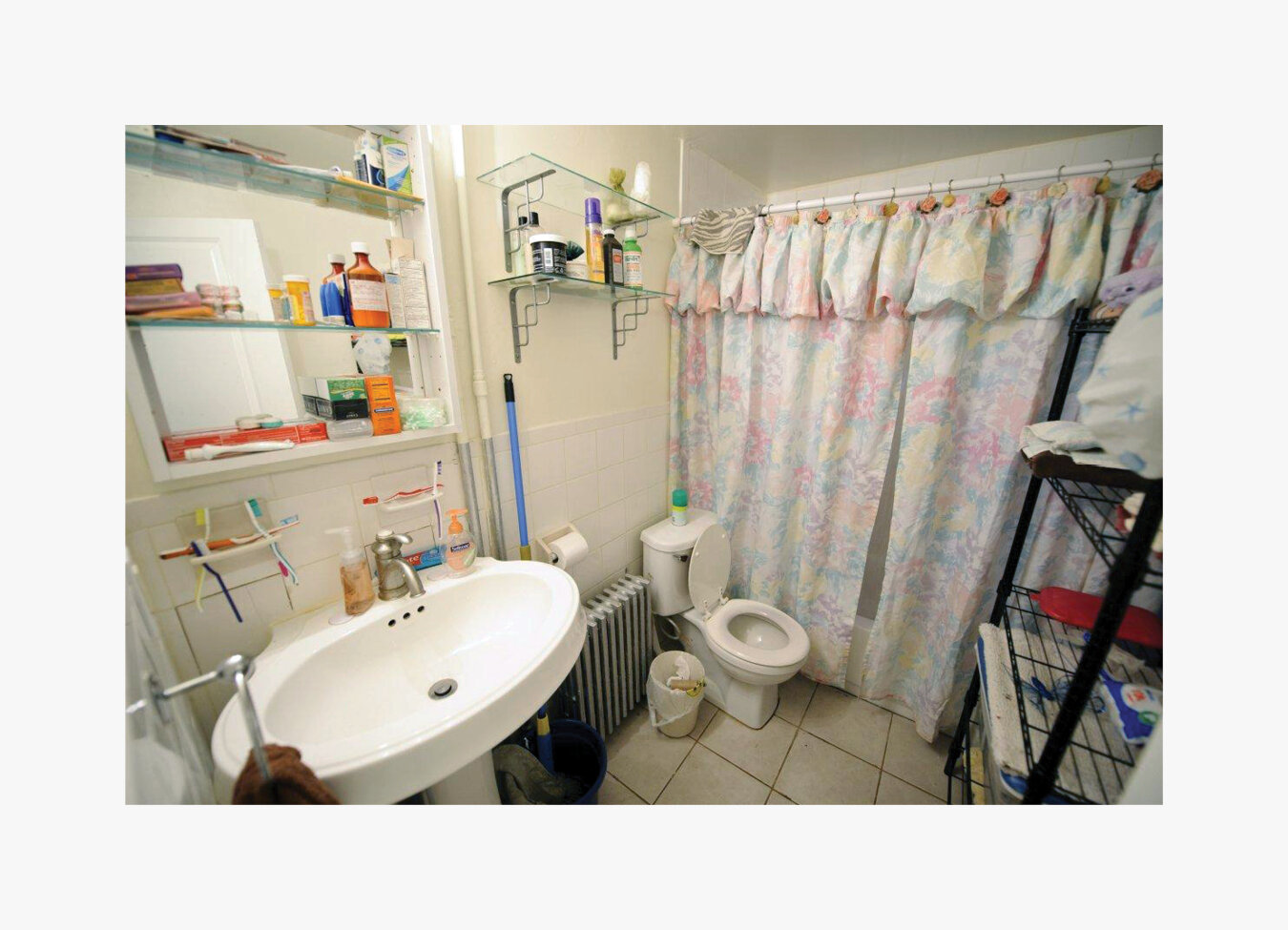

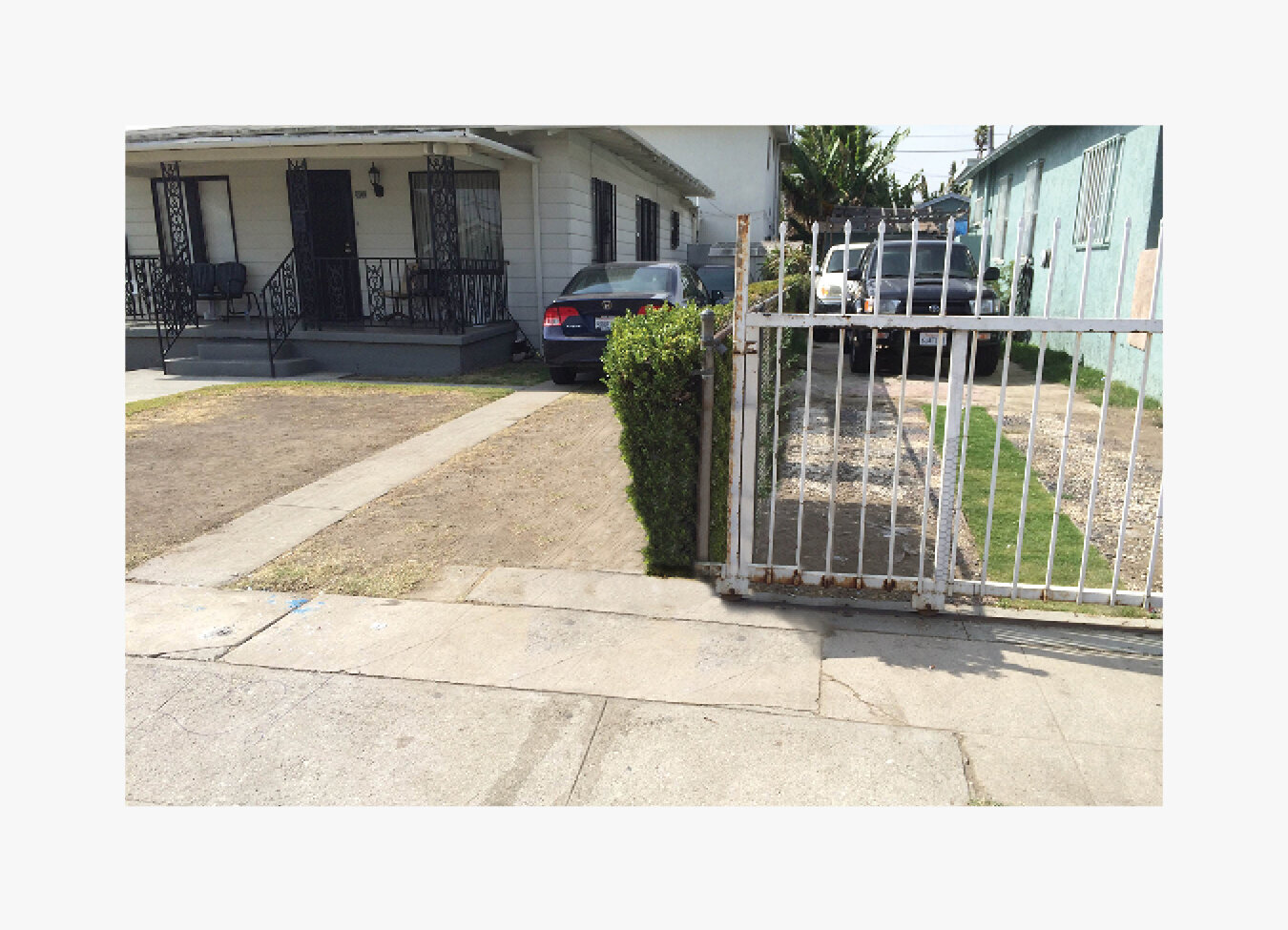

Here is where the disruptive work of Ashley M. Freeby’s Many Thousands Gone finds its force. It invites us to reimagine the landscapes of police—and police-empowered—brutality against Black and Brown people and all people of color. Freeby’s image-making practice visually confronts us with the geographies of Black and Brown life in a moment when death drives the news media coverage. Her digitally altered photographs present the histories of a present time that is changed and charged by violence but not reducible to it.

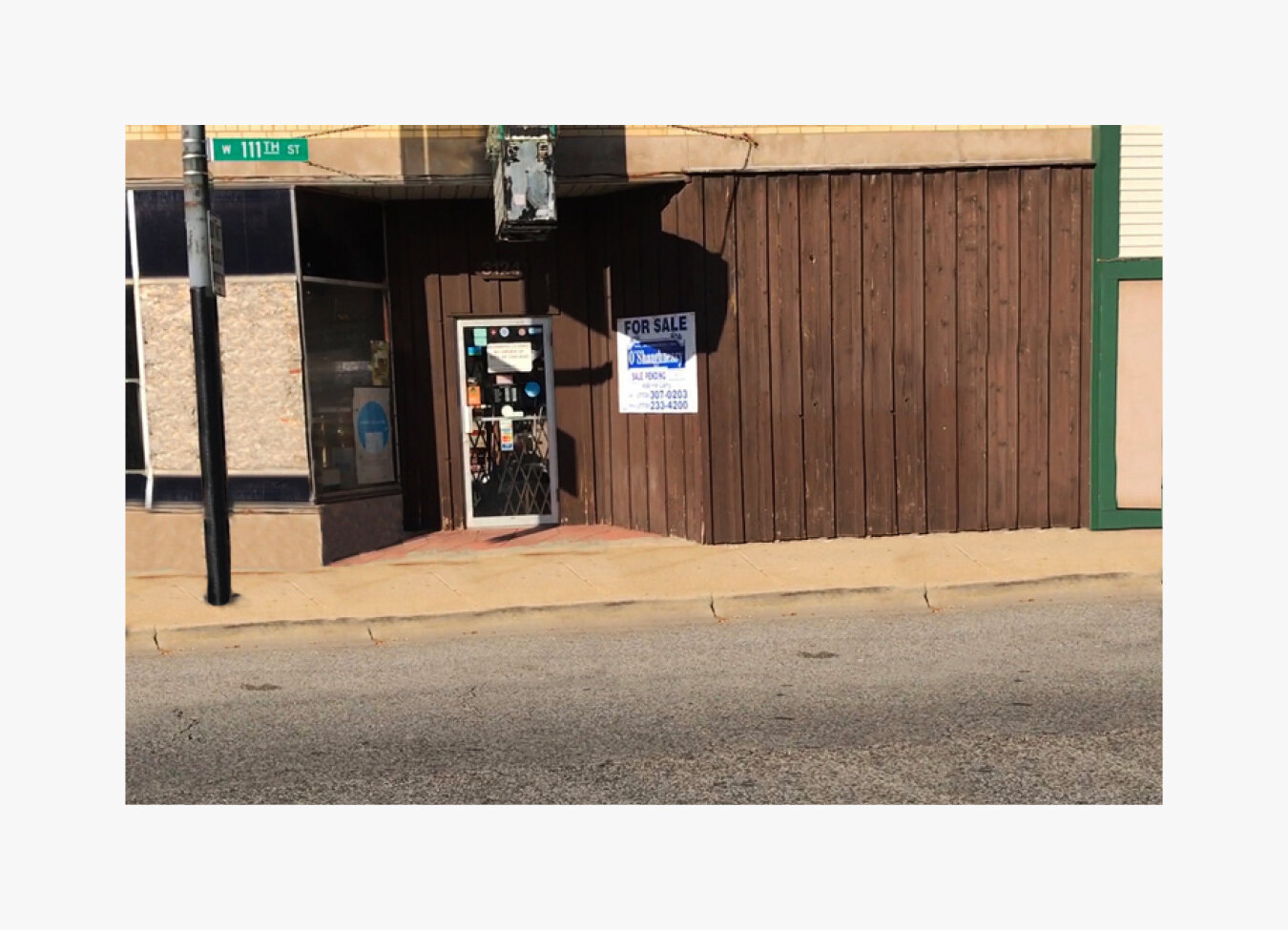

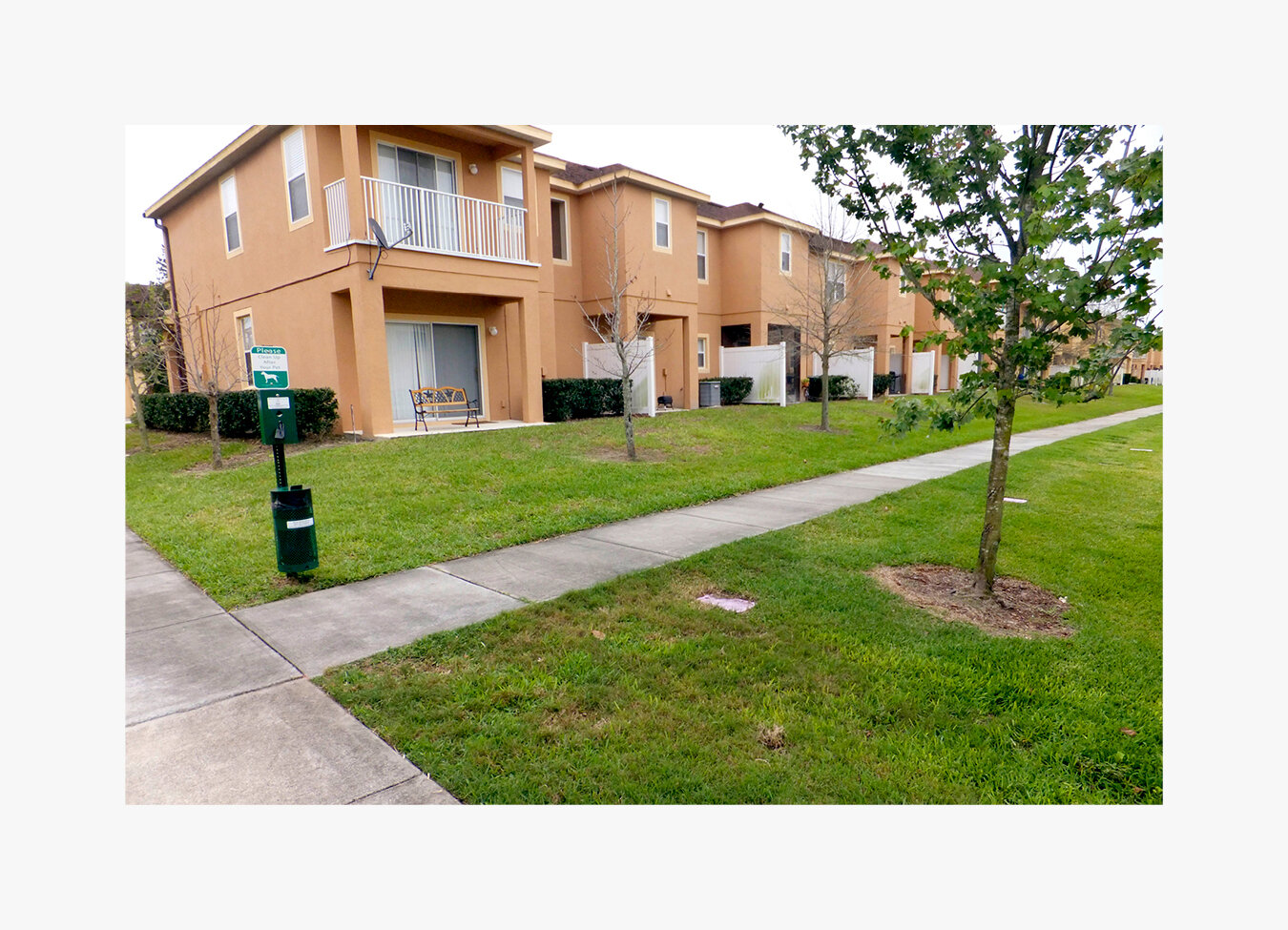

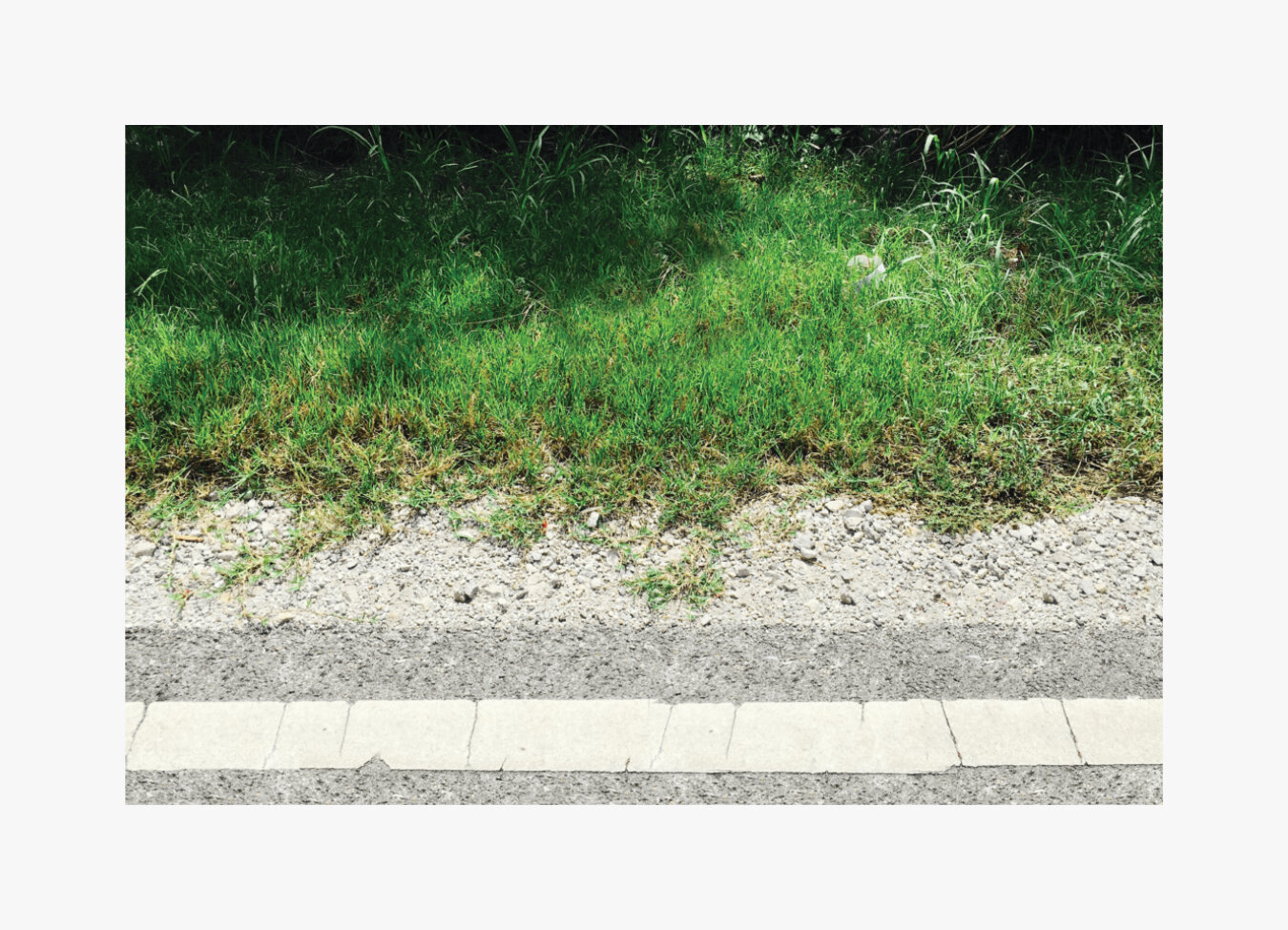

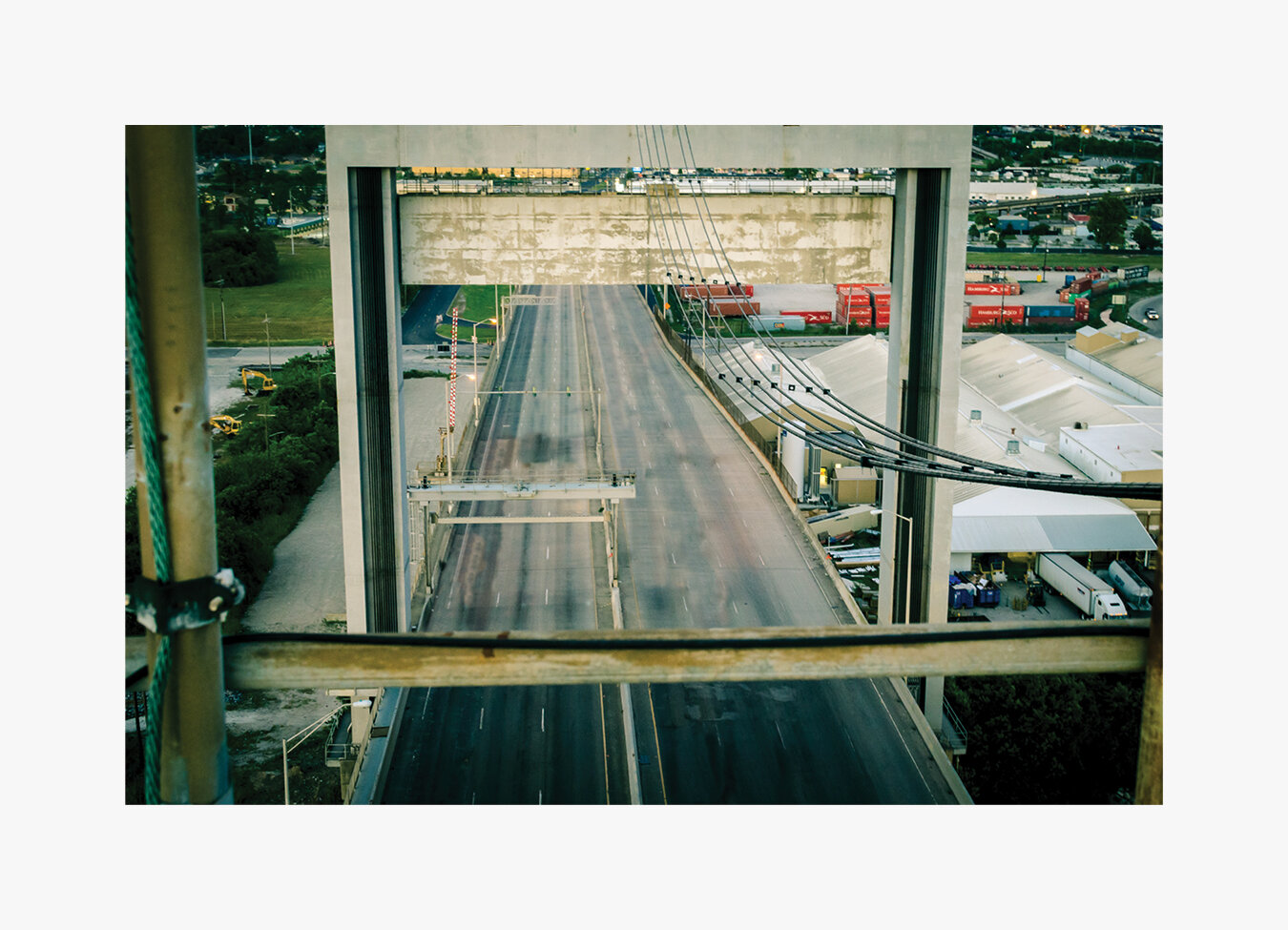

This maneuvering is deceptive. Stripped of the digital banners appearing in bright primary colors, the pixelated text filling the lower third of the picture plane, and the crawling updates that refresh by the minute, the images extracted from news coverage in Freeby’s work seem comparatively quiet and almost peaceful. The places she features are often communal and overwhelmingly residential. The street views assembled in the collection feature wide shots of cozy outdoor spaces: sidewalks directly in front of bi-level or apartment homes; lawns; parks; narrow doorways from which children emerge to play in the early evening’s fading light. In Freeby’s documentation, these sites are not simply crime scenes. They are spaces that belong to neighbors, to a civic multitude that tends and toils and grieves and grows. Like Ken Gonzales-Day’s critical elision of lynched bodies in the photographic series Erased Lynching, Freeby’s work is haunted by our shared historical repertoire of racial terror. It updates our archive with subtle alterations that offer a history of a more just future, a future in which the killings perhaps never were.

Think again of the photograph that heralds George Floyd’s final thwarted breaths, that captures Derek Chauvin’s death kneel. Think, too, on the grim witness of officers J. Alexander Kueng, Thomas Lane, and Tou Thao, variably visible in some versions of the photograph or otherwise present just beyond the frame. Can you picture them? Can you envision the buildings surrounding the scene? Do you imagine a clear day or an overcast sky? Do you see the crosswalk at the intersection of East 38th street and Chicago Avenue? Do you notice the squat brick building that houses the Cup Foods grocery, with its tidy rows of fresh and staple foods and its loping takeout counter? Do you remember the low gray awning of the Speedway gas station slicing across the skyline? Where in the Minneapolis cityscape does this tableau take place? And if you cannot recall, does that mean that it happened—that it happens—in some no man’s land, or everywhere?

This is what Ashley M. Freeby makes us see: neither first responders nor investigative teams nor victims nor assailants. Neither cop cars nor action news nor local crime statistics. Rather, Freeby gifts us with a world that was and also never-was. Freeby’s work charts a world that we simultaneously make and re-make with our memory and which we might, hopefully, sanctify with our anger and watchful resolve to live out the mattering of Black life, such as it is.[2]

[1]

Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-making in Nineteenth-century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997) 4.

[2]

Here, I gesture toward Calvin Warren’s careful grappling with questions of the nature of Black being and the mattering of Black life. Resolutely unconvinced that liberal humanism’s framing of being provides a viable possibility for Black existence beyond social and ontological death, Warren maintains that Blackness provides the rejected but necessary fulcrum on which Western notions of the human being depend. Following Warren’s line of argument in what is, perhaps, a contrary direction, I want to highlight need for a critical re-working of the terms by which we name Black existence and also join in the ever-evolving work of making that existence matter. For more, see also: Calvin L. Warren, Ontological Terror: Blackness, Nihilism, and Emancipation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018).

[3] “Officer Jeronimo Yanez has a court appearance Friday in the shooting death of Philando Castile. Here, investigators take photos of the shooting scene on Larpenteur Avenue in Falcon Heights in July. Christopher Juhn for MPR News file” SOURCE LINK

About Our Writer

Nicole Ivy, PhD, is a historical thinker and professional futurist who is passionate about the arts and social change. Her professional and scholarly interests include strategic foresight, public history, visual culture, and inclusive change management. She earned her B.A. in English from the University of Florida and her joint Ph.D. in African American Studies and American Studies from Yale University. Having begun her work in the museum field as an Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Graduate Fellow at the African American Museum in Philadelphia, she has held several inaugural positions at the American Alliance of Museums, including serving as its first Director of Inclusion. In addition to her work in the museum field, she has held numerous academic appointments. She was a Visiting Assistant Professor in the History Department at Indiana University, Bloomington (IUB) and a postdoctoral fellow of the Center for Research on Race and Ethnicity in Society (CRRES) at IUB. She is an Assistant Professor of American Studies at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

Many Thousands Gone Series

to view the 39 images + notes from my artist journal click the button below

Segment 148

[week 3] Segment 148 is dedicated to George Floyd.

This segment will be documented every week to reveal the growth and decay over 7 weeks.